the two journeys in every story

plus a free event for novelists

During the fall of 2020, when we were largely confined to our houses, I signed up for a lecture from Emily Stone on the novel Rebecca, which is a gothic novel about a young woman who is largely confined to a house. Before Emily, I hadn’t really thought much about gothic novels as a genre. After Emily, I realized that gothic novels are actually one of my longtime preoccupations and in fact I had already tried to write one—Self Care began as a 21st century retelling of The Yellow Wallpaper with a digital detox for a burnt out girlboss instead of a Victorian rest cure.

I still have my notes from Emily’s Rebecca lecture:

gothic is both huge swelling romance + interior mental illness, a lot of gaslighting

need a good house for a gothic, and a reason to keep the character in the house

earlier time: the woman couldn’t really leave the house

Where’s the protagonist of Rebecca gonna go? She has no choice but to be in service

Is the house trying to kill you? (Get Out)

When she said you need “a reason to keep the character in the house,” I flashed on Taylor Lorenz’s New York Times article, from earlier that same year, about a Los Angeles mansion that was turned into a TikTok hype house.

I spent the next four and a half years writing a gothic novel about the internet as the ultimate haunted house. You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.

This week, I spoke to Emily about gothic novels, psychological suspense, and the difference between external desire and internal need. If you’re working on a novel right now, I highly recommend her Scene Study class (note to my past Plot Curious students: Emily is the one who taught me Scene & Sequel!)

Emily and I will also be doing a FREE event together—all the details at the bottom of this Q&A.

1. Emily, I feel like we're in a very gothic moment. I was talking to my friend Lily last week about my obsession with abusive and controlling mommy vloggers and she quipped, "YouTube Gothic." I still have my notes from your Rebecca lecture, when you told us "you need a good house for a gothic, and a reason to keep the character in the house." Can you give us the recipe for a gothic novel? What are the ingredients?

The original Gothic novels (the Northanger Canon), such as Castle of Otranto, The Monk, were written when the Enlightenment had burned itself out. Romanticism's rise came from the failure of classicism to explain the chaos. In other words, the call was coming from inside the house. Remember, early Gothic (which is not what we think of when we think of Gothic, rather its predecessor) was closer to horror and fantasy, with a side order of incest. But when you think of later Gothic from Jane Eyre to Wuthering Heights to Rebecca to Flowers in the Attic, I would say that you need the following ingredients: A big ol’ decaying estate/house; icky weather; forced isolation; intense, unrelenting emotion leading to downward spiral; the supernatural amping up an element of the unknown in some way; spooky settings and possible ghosts. The key here is that the house is now a decidedly UNSAFE space.

2. Why is the house so important in a gothic novel and what can it represent?

I read somewhere once in gender theory that the castle is a space of patriarchal repressive authority. Think of the king of the castle. Think Edward Fairfax Rochester. Even the beast in Beauty and the Beast. Or the minotaur in the labyrinth. But the castle can also serve as an ungendered psychic dream space where we meet a range of familiar archetypes: the maiden, the attractive, enigmatic older man (the beast), the chatelaine or old crone—the keeper of the keys and secrets. Of course, the house is also considered a domestic space, and society associated it with womenfolk and the womanly arts. Gothic flips this notion on its head. Now the house is a haunted house. The dream equals reality.

In Gothic novels, the protagonist is generally a woman trapped in the house by an unseen force. There is also an idea that the house is the protagonist herself, and she is trapped in her own mind and psychic dream space. If you are trapped in the house, and the house is you, you must find a way to break the house/yourself. How do you turn your nightmare into something positive? In many cases, you can’t. That’s why in many Gothic novels, the house usually burns down at the end. There is a complete reckoning.

3. I read a report from the London Book Fair that noted more interest in "female-led psychological suspense." (Have these ever gone out of style?) Why do we love this genre so much? Why can we re-read Rebecca and still enjoy it, even if we already know the twist?

First of all, Rebecca is an ideal gothic. It reads like a dream. The second Mrs. de Winter is in some way the perfect protagonist because of her namelessness. I often think this as I watch murder shows on TV, which feature mutilated, nameless female bodies and male killers. I think about how we are culturally obsessed with dead women and murdering, scary men. The psychic collective dream space is about waking up in the castle or the house and realizing that the murderous brute is sleeping in the bed with you.

Regarding Rebecca, you also have the bonus of Mrs. Danvers, one of the best characters of all time. I first read the book when I was in the sixth grade. I remember loving Maxim and the second Mrs. de Winter, and my romantic heart wanted them to stay together forever. I rooted for them. Now that I am in my wise witch phase, I see the real twist happens after the second Mrs. de Winter finds out about the murder. That’s when she becomes the queen of the castle. The way du Maurier manages the double helix of everyone’s ghosts and core wounds is a craft class unto itself.

4. My friend Alizah once told me there are only two stories in the world: fish out of water and a knock at the door. The gothic has both: the newcomer to the house. Can you tell us about the Greek concept of xenia and how it gets violated in Rebecca?

I might add a third aphorism: don’t bite the hand (of God) that feeds you. I mention God here not out of my religiousness, but to mention an offshoot of “knock at the door,” which pertains to the Greek concept of xenia, the sacred rule of guest friendship. If a guest knocked at your door, you had to let them in, bathe, feed, and put them up for the night. Xenia was considered a religious, sacred obligation. In the fifth century, it was a hardcoded interpersonal metric and the core of instinctive empathy. In a sense, it established a character’s values ( private and public). This universal code for morality in any world—Greeks, the Bible, Eastern religions—was essentially about the generosity or kindness you show to those who come to your HOME. The Trojan War resulted from a violation of xenia. Paris, from the house of Priam of Troy, was a guest of Menelaus, King of Mycenaean Sparta, but transgressed the bounds of xenia by abducting Helen (sister of Clytemnestra). Therefore, the Achaeans avenged this transgression. Heroes honor xenia without fail and help others do likewise. Villains violate xenia, often and awfully.

Rebecca violated xenia by cheating on Max with her cousin. You only get to call xenia if you show it. After you violate xenia, anything can happen. It’s essentially fair. The xenia you show your king differs from the xenia you owe your wife. Xenia isn’t easy. It’s tough to walk that tightrope.

5. When I teach plot structure, I use John Truby's method, and he uses the word "opponent" to describe the antagonist. The most common question I get from students is "but what if my main character's opponent is herself?" I try to help my students understand the difference between the external battle the main character is waging (to reach a goal) and the internal battle to overcome some kind of psychological need. How do you help your own students learn to combine external goals with psychological battles in their novels?

Story consultant Michael Hague talks about something he calls "Identity to Essence," which best answers this question. He says there are two journeys in a story of any depth. There’s an outer journey of accomplishment—the hero achieves a tactile GOAL we can envision: Get the girl/get the guy/stop the killer/get the Ring. And an inner journey of transformation. You (the writer) need to ask yourself what the character’s wound/void is that they think they have put behind them at the top of the story, but haven’t. AKA the core wound. This is the hero’s inner journey. The external plot has to propel the character through their internal journey. It has to impede and help them. Meanwhile, the core wound does the same with the external journey. It's a dance.

People spend too much time bogged down in details like clothing, eye color, body odor, and astrological signs when the key thing to focus on is what my character wants. What is the book's goal? What is stopping them from getting it? In a love story, the obstacle can be external, and it can also be internal (core wound), but it also has to be believable. You don’t want the obstacle to feel arbitrary or like a plot device. The Gothic provides significant obstacles. The house is an obstacle. The crone is an obstacle. The dead wife clanking around in the attic is an obstacle. The mind of the woman who is trapped in the house is an obstacle, too. Why did she allow this? How did she end up there? How is she in the house? How will she escape her past self to emerge as her new self, her essence? The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson is a paradigmatic example of house as woman in a psychic dream space, as is We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which btw, is a perfect novel. It gets at the heart of what Gothic became, which is a blended smoothie of horror and romance.

On Wednesday May 7 at 8pm EST, I’m hosting Emily for a FREE event to take your questions about plot structure.

You do NOT have to be a premium subscriber to join us. This one’s open to everyone. Just fill out this short registration form and I will email you the Zoom link (give me a day or two to send you the link—it isn’t automatic!)

This one won’t be recorded.

If you can’t make it on Wednesday night, Emily will take your questions in the comments of this post.

Chat Room

My next Chat Room will be on Thursday May 15 at 1pm EST with Madeline McIntosh, former CEO of Penguin Random House US and the co-founder, CEO, and publisher of Authors Equity. Save the date! 💎 My diamond medallion members will receive the link to the Zoom on the morning of May 15. 💎

Highlights

You might think I never leave the internet but sometimes I do—in order to meet people I know from the internet, and prove that I exist in a physical form.

This week, I met my client

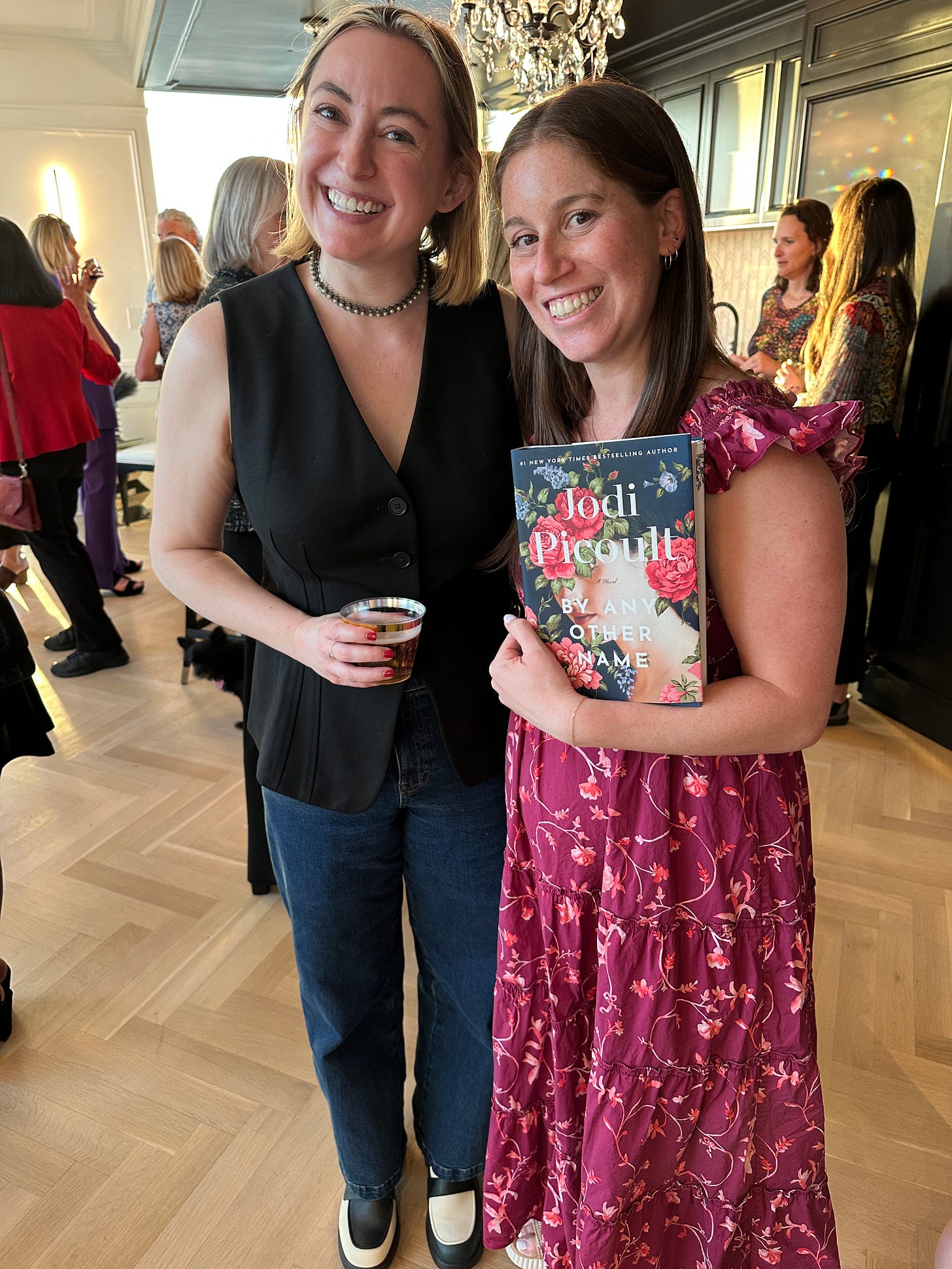

for the first time in person, at the KGB Red Room. Melanie’s novel Nightswimming, a police procedural set in gritty Paterson, NJ in the late 1970s, comes out soon. (for any crime fiction afficianados, message me if you’d like to have Melanie on your podcast/Substack, etc.!)I also met bookfluencer Kayla Kleinman. Kayla came to a Zoom event for Self Care in the summer of 2020, when all we had available to us were… Zoom events. I finally got to meet her IRL at the party my client

threw for the novelist Jodi Picoult, to benefit the Authors Guild Foundation. Definitely follow Brisa if you love Broadway and want recommendations from an insider!On Thursday, I took the train to Philly to teach plot structure to Drexel MFA students, who were lovely and enthusiastic and laughed at all my jokes. This is me with the director of the program, Nomi Eve. I did not meet Nomi on the internet; I actually met her in France last summer when I was teaching for

in Collioure. If you’d like to have me Zoom in as a guest speaker for your students this fall (hint: my new TikTok novel would be a juicy read for a media studies course), message me.

I can’t make the event with Emily so I’m just commenting to say HI EMILY. Also, I 100% need a t shirt that says CONTENT across the boobs. In fact, maybe you ought to give me yours.

"The house is the woman”: It reframes Rebecca in a chillingly intimate manner. Manor pun not intended.

Not just a woman trapped by circumstance, but a psyche walled in by ghosts -- of other women, of roles she never chose, of desires she’s not allowed to have. The second Mrs. de Winter’s transformation, post-reveal, into “queen of the castle” hits even harder when you realize the house was her all along.

And the idea of the internet as the ultimate haunted house -- inescapable, ever-watching, endlessly performative -- feels like a perfect modern gothic setting. Thank you for a conversation that connects literary tradition to our weird, wired now.