Come with me in my time machine, as we travel to the 1980s, the good old days of publishing, before Twitter or TikTok or the phrase “personal brand” had even been invented, when a publisher could make an author’s career.

In 1979, James Wilcox was a talented thirty-year-old associate editor at Doubleday, who secretly dreamed of being a full-time literary novelist. Encouraged by his colleague Toni Morrison, who had the office down the hall, Wilcox gave his notice, rented the cheapest apartment he could find, and spent the next year writing and submitting short stories to the New Yorker.

At the end of that year, the fiction editor called him up to say they were taking one of the stories and would pay him $2,200 for it. Motivated by this lucky break, Wilcox started writing a novel set in the same fictional town (Tula Springs, Louisiana) as his short story. That first novel, titled Modern Baptists, was acquired by Dial Press for $6,500.

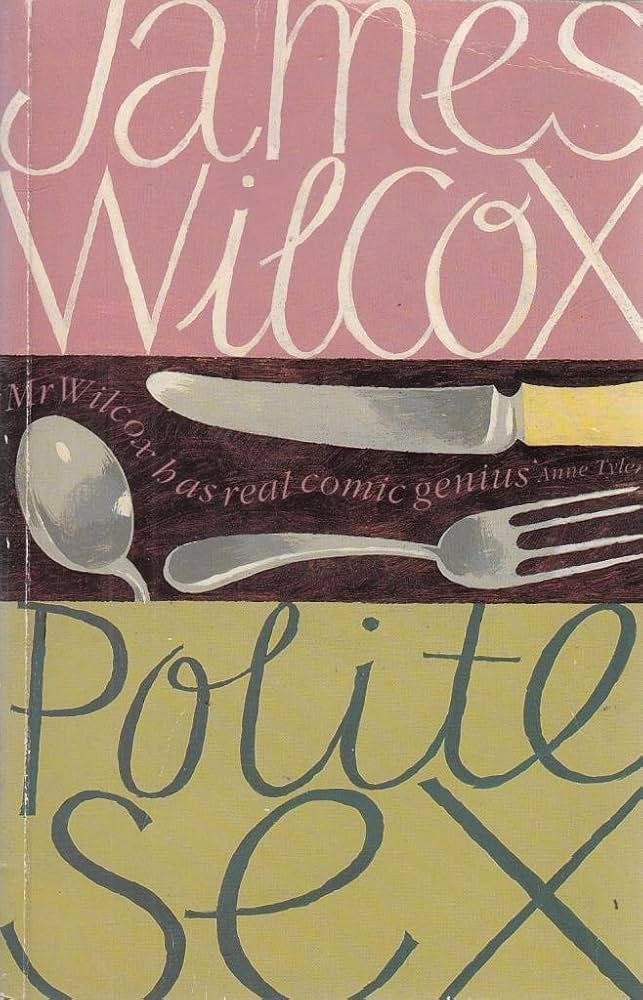

It was released in 1983 to unanimous critical acclaim, including a front page review in the New York Times Book Review by Anne Tyler, who said Wilcox had “a real comic genius.” The book sold 11,000 copies in hardcover and his literary agent was able to negotiate a $27,500 advance for his next novel. Wilcox felt so stable in his new career as a novelist that he stopped writing short stories.

I had never heard of James Wilcox before I read this profile of him from 1994 by James B. Stewart (thank you to

for sharing it with me). What struck me as I read the piece was not how different things used to be for literary novelists, but in fact how little has changed, in terms of author expectations and what a publisher can actually control or deliver.Like many novelists, Wilcox assumed the success of his first book was an indicator… of future success. He thought he was on an escalator going up!

His sophomore novel, North Gladiola (1985), never came close to earning out its advance, but Wilcox was able to sign with a hot shot agent, Binky Urban, who negotiated a two-book deal for $70,000. For a couple of years, the scrupulously frugal Wilcox earned enough money to occasionally take a taxi, or dine out.

His third novel sold fewer than 5,000 copies. His fourth novel, though well received, didn’t break the dismal sales pattern. Stewart writes that his publisher’s sales force “was growing more and more discouraged about Wilcox’s prospects. ‘They’d look on their computers and see that his last book only sold three, so they’d say, “We’ll only take two this time,”’ Kot [Wilcox’s editor] says.”

Editor and agent strategized with Wilcox on how he could reach the young, trendy urban market that was going for Jay McInerney. So Wilcox wrote a novel where a character from Small Town, Louisiana moves to the Big City.

His fans hated it. “Not only did Polite Sex fail to attract the urban readers Kot and Urban had hoped for but it seemed to alienate his core group of Southerners,” Stewart tells us.

Polite Sex sold only three thousand copies.

By the end of the profile in the New Yorker, Wilcox has been offered a $10,000 advance for his latest book. His agent begs him to consider his audience:

A problem with selling his books is who will buy them. That’s what a bookseller asks. Literary fiction is not selling well. You need a target market. Women buy books, but his aren’t women’s books. It’s pathetic. Why can’t you just write good books? But there’s too much competition for people’s attention. I told him, “We have to have something.”

What does Wilcox do with this advice?

“It’s so little money that I’m going to write this exactly the way I want,” Wilcox told Stewart. “I feel a burden has been lifted. When I was getting the pages together, I was worried. Can Binky sell this? Now I know it’s never going to be a big commercial book. In a way, I’m much happier.”

I know you’re hoping for a happily ever after: that writing the novel that was truly in his heart, unshackled from commercial imperatives, led Wilcox to the biggest success of his career. But after visiting his Wikipedia page and connecting the dots, I figured out that, unable to support himself as a literary novelist, he went into academia.

Even though Wilcox was publishing a novel every two years for a decade, and he had loyal fans who loved Tula Springs (the New Yorker profile concludes with a touching fan letter), he was unable to maintain a connection with his audience, or grow his audience. He stopped writing short stories, which would have at least kept him in the mind of his readers, in between novels.

The novelists reading this right now have a great advantage over Wilcox: you can talk to your audience. You can find out who they are. You can ask them questions. You can send them messages. You can let them know when there’s a new release in your own personal Tula Springs literary universe.

What if, hear me out, you’re not actually living through the worst era to be a literary novelist? What if this one is the best?

When the New Yorker profile came out, I was ten years old.

Ten years later, I started building an audience on Livejournal for my short stories and poetry. Several of my followers were high school students; one of them would later intern at the New Yorker and refer me for a job there. Another one of my followers was a teenage boy who plagiarized one of my short stories and published it in his high school literary magazine. The teenage girls who followed me discovered the theft and outed him. I received an apology email from the student editor of the lit journal and thought it was funny and flattering that I was good enough to copy.

In 2012, when my first novel came out, one literary outlet in particular was giving a lot of positive attention to my debut. I found out that the guy who ran the website’s social media accounts was once my teenage plagiarist. This was his way of making amends. (He still works in social media—I read an interview with him in another Substack I follow! I wish him nothing but the best and only tell the story because it’s a great story.)

Now I’m forty years old. I’ve been building audiences on the internet for twenty years. I’ve survived the life and death cycle of multiple platforms (Livejournal, Tumblr, Twitter, now TikTok). I’ve sold six books during this time and while I would love for my publisher to be a collaborative partner in the launch of my next book, and pull marketing levers I don’t have access to, I don’t expect them to know my audience better than I do.

We tell novelists they don’t need platforms and then when no one buys their novels, we tell them it’s not their fault. There’s nothing they could have done. I’m starting to wonder if these two things might be connected.

Exhibit A is this sad letter to Ask Polly from December:

Hi Polly,

I've been an admirer of your column for over a decade, and today I am writing to you with a problem that I have tried to fix with relentless amounts of positive thinking, self-pep talks, and marijuana. But I just can't seem to shake it off, so here I go.

I feel like an utter and complete failure. I published a novel this year with a big publishing house, but it's not sold many copies and has gotten minimal press. I have tried my best to hustle, emailing bookstores to ask if they want to do events with me, reaching out to influencers myself, checking in with the book's publicity team, but none of it has helped. I have tried building my own audience on Substack, but the numbers are low and will not budge. I worked so hard on my book. I stand by it as a work of art; I know it's good. But I am scared that with these low numbers, I will never be able to publish a book again. And there is nothing I want to do more than write books.

I was genuinely shocked to read Heather Havrilesky’s response:

Blaming yourself for not selling books is like blaming yourself for aging. It’s irrational. Books don’t sell, period. Have you ever skimmed the best seller list? If a book is truly great, it’s almost guaranteed not to sell. You’re calling yourself a failure for things that are out of your control. That’s the kind of unreasonable position you start to take when you eat bad noises for way too long without noticing it.

Blaming yourself for not selling books is like blaming yourself for aging.

It’s actually not at all like aging, an inescapable biological process.

The thought “nothing I do makes any difference” is—and I’m not joking—a symptom of depression. Why would you, in your capacity as an advice columnist, send the message nothing you’re doing makes any difference?

If Heather Havrilesky doesn’t believe in building a platform or marketing to one’s own audience, why does she promote her books to her Substack audience?

As a stubborn pragmatist working in book publishing, I absolutely refuse to believe that there’s nothing that authors can do to market their own books. I refuse.

I fully realize that Heather Havrilesky’s job is to offer counsel for the soul, not give career advice, but here is I would tell “Author Down,” if I could:

You are already doing more than most novelists, by writing a newsletter and doing your own outreach to book influencers. You’re ahead of the curve, and I know you’re disappointed you haven’t seen more results from your efforts, but the paperback release gives you a rare second chance. (Authors who publish in paperback original, like me, don’t get that second opportunity.)

I would double-down on what has worked the best for you in launching the hardcover. Interview your most devoted subscribers on what kind of content they wish you were publishing more of (or look at your post statistics for clues). Check the comments sections of your favorite book influencer’s posts to find accounts of readers who like similar books. Pick one platform that you don’t hate spending time on and make new friends there who you can collaborate with, so you can borrow their audience to promote the paperback.

Just as you learned the craft of writing, you can learn marketing. You can get better at it. It’s too soon to give up, or in the words of one of my clients, “it’s too late to quit.”

BOOKPRTY

One of the funniest women on Substack,

, is hosting a party next Sunday, the 26, for Self Care, the novel I wrote that always be timely because women will always be putting stuff on their faces to quiet their inner despair. We’ll talk about the book but we’ll also gossip. Become a paid subscriber of to join us.Upcoming Events

Join me on January 23rd for a conversation with Jackson Howard, who acquires literary fiction and nonfiction for FSG. I’m going to be asking him about what he thinks about the relationship between MFA programs and the publishing industry, and my favorite topic: platforms for novelists.

On January 29th, I’ll be speaking with literary agent Kara Rota, who represents memoir plus, as well as pop culture, body/mind/spirit, and parenting books.

Leah, what a beautiful post! I’m so honored to be included here! I would only urge everyone here to read my reply in that Ask Polly column and see if you come away with the sense that by instructing the letter writer not to blame herself for her lack of sales, I’m urging her to give up or to believe that there's nothing she can do. She, like so many authors, believes that her bad sales numbers mean she’s a failure, and I tell her:

“You did what you set out to do. You were successful. You even got paid for it. You even published it. You even worked your ass off to promote it. These are all huge, rare successes.”

If I replied by telling her all the things she could’ve done or should do next time, I would’ve sounded like the mother in “Election” (great movie, btw), telling Reese Witherspoon’s crying high school overachiever, “Maybe you should’ve made more posters.”

Instead, my aim was to empathize with her and let her know that she’s not remotely alone in feeling the way she does. And I’d argue that it’s healthy and even oddly helpful for authors to face the uncomfortable reality that no matter how many marketing dollars are behind their books and no matter how much effort they put into promotion, there’s a good chance that they won’t sell as well as they want them to. Grappling with that reality is *always* difficult and discouraging, but you can’t let it prevent you from throwing your entire body and mind into your work, your art, your passion, and your promotional efforts, too. You can’t let the world’s bad noises about commerce trick you into believing that you’re a failure because of sales numbers.

Writing and promoting a book is hard. It’s a victory to get through that process. Or as I wrote at the end of my column: “You write because you believe in it. You still believe, even now. You crave love, and that part of you isn’t humiliating. It’s sad and pure and true. It’s a gift.”

https://www.ask-polly.com/p/i-published-a-novel-and-no-one-cares

But speaking of gifts, I loved your promotional advice here. I don’t know if you answer advice letters from authors, but if you don’t, maybe you should because you’d obviously be great at it! Once I finish my next book, I will be back to soak up allllll of your guidance! Thanks for bringing so much optimism, joy, and humor to this subject, and thanks again for discussing my column in this excellent post.

Wow, I loved reading this. Jim Wilcox was a professor of fiction and head of the MFA program at LSU when I was there. I was doing an MFA in poetry so I never had him as a professor and never knew his story. But he's a really lovely man. This whole piece gives such an interesting new perspective to the old, sad, woe-is-me story of being a writer today — thank you for that. Maybe it IS one of the best eras to be a literary novelist (or poet, or writer of whatever genre)!