give away something valuable

I spent this week in a kind of fugue state, completely obsessed with Tavi Gevinson’s 75-page self-published fanzine, titled Fan Fiction: A satire, about Taylor Swift. If that sentence is incomprehensible to you, let me put it like this: there’s a self-published PDF on the internet that’s like Nabokov’s novel Pale Fire, only about a female writer’s obsession with Taylor Swift, instead of a male academic’s obsession with a dead poet.

When I wrote about it for LitHub, I said this:

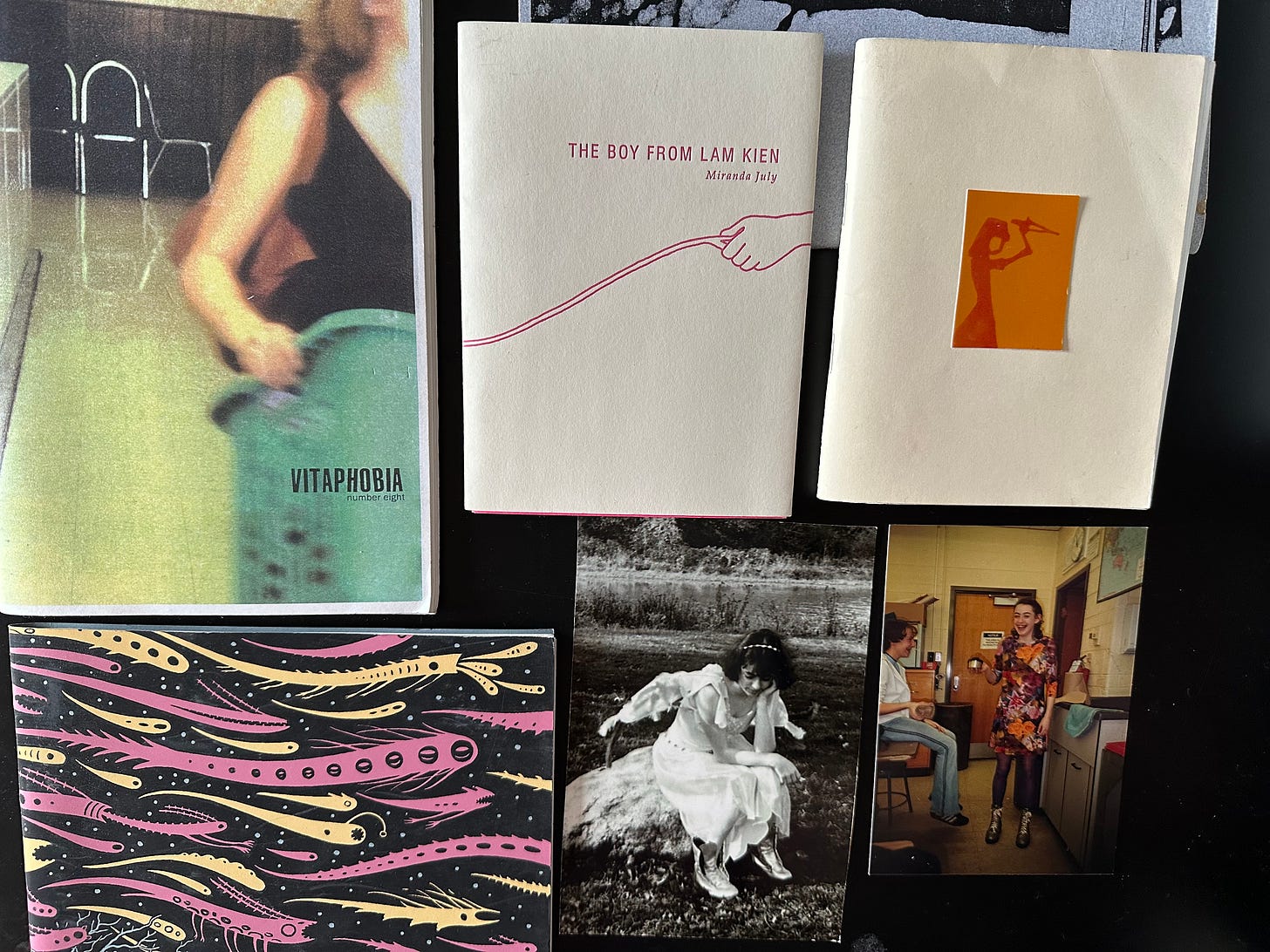

Although I don’t idolize any musician, writer, or artist in the way tens of millions idolize Taylor, I harbor my own obsessions. One is my nostalgia for the early 2000s internet, where I came of age, following Tavi’s predecessors, moody poets and cryptic self-portrait photographers on Livejournal. I collected zines and chapbooks. I believed art and poetry were meant to be shared, among other young women, like an artist collective enabled by the internet, before I knew anything about branding or marketing or book advances. Before Instagram replaced the mall. Tavi’s zine, distributed for free, reminds me of the time in my life before I began, out of economic necessity, to treat my own art as a business.

I owe my writing career to the internet. I was publishing short stories and poetry on Livejournal as a high school drop out. One of my followers, who had an MFA, gave me a tip: if I stopped self-publishing my poetry, I could submit my poems to “literary journals” (this was the first I’d ever heard of such a thing). By the time I was 27, I had a three-page CV, four published poetry chapbooks, and two forthcoming books. I graduated from Brooklyn College, as an adult student, the year those books came out.

I shared a lot of work for free—before I was ever paid for my creative writing.

What I have witnessed over the past decade or so is a vocal demand for creative writers to be paid for their “labor,” meaning that writers deserve financial compensation for every poem or short story or braided essay that appears on a literary website or in the pages of a printed literary journal. This has resulted in the closing of almost every single online lit mag that published me as a young poet.

Although I fully agree that corporations should fairly compensate writers for freelance work (and pay their employees! and pay their interns!), I’m disheartened at the loss of so many volunteer-run passion projects that never could have afforded to pay themselves a penny—let alone every poet.

In my view, we’ve lost that fizzy, fun DIY spirit that I discovered in zine culture in the late ’90s, and in blogging culture of the early ’00s.

Tavi’s fanzine this week brought it back for me. When Vulture asked her why she didn’t publish this as a real book (presumably for money!), she said:

I am just really lucky that I can do something like this. I’m glad that I can spend a lot of time on something for fun, and it was similar with my blog and with Rookie, which was so challenging financially to run as a business. I love having a physical copy of a piece of writing and to know that it would be tactile and that anyone could just print their own. And going back to the different contexts and considerations around writing about real people, I do think there’s a change if you are profiting in some way. Obviously if I publish work and people like it, I benefit from that. But for the spirit of this to be actual fan fiction that is accessible and in the spirit of fan zines — that ended up being important to me.

I know that a lot of writers believe that they are putting out so much content “for free” already but a lot of it is lifestyle content (photos of what you ate and what you wore while you were eating it) and self-promo. It isn’t valuable.

Young writers like Hailey Denise Colborn, who I interviewed for LitHub, are doing exactly what I did in the early 2000s: publishing directly to their audience, instead of wasting time and energy submitting work to obscure magazines that take 12 months to respond and are only read by other writers who aspire to appear in their pages.

I think we can use Tavi as an example of someone who is successful and accomplished enough to make anything she does “for profit” and yet she still honors that inner teenage girl who got her start sharing her writing for free on the internet.

In “Write Till You Drop,” Annie Dillard says:

One of the few things I know about writing is this: spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.

Tavi gave it away.

What could you give away? What are you hoarding for later—for a better opportunity, for more money, for more prestige?

I’ll leave you with a few examples of writers giving it away1:

My client Melanie Anagnos spent months doing deep research into a media controversy over Playboy in the late 1970s and the second-wave feminist backlash against women who posed for the magazine. The final piece was so long that she decided to serialize it, for free, on Substack. You can read the introduction (and subequent issues) here.

My client amelia wilson figured out how to turn her Substack into a destination for recommendations—a valuable service for her readers looking for what to watch on TV, or what to listen to on a road trip.

When I started writing poems again for the first time in nearly a decade, I started publishing them on Substack. Those poems became my fifth book What to Miss When, which I was able to sell on proposal

There are more examples of writers producing great content in the comments thread of this post:

Also of Interest

I loved Meghan Daum’s interview with Sloane Crosley about working in publishing under Russell Perreault in the 2000s

A Q&A with Lauren Oyler about how she uses the internet over at Embedded

Sorry, I know this looks like an advertisement for Substack but it’s a writer-friendly platform that reminds me of the blogs of my youth!

Thank you for the mention! I think there's an interesting tension between giving creative work away (and doing it out of love) and getting fairly paid for your hard work. As a writer at the beginning of my career I often think of myself as a "start-up" and tell myself that the money will come later, once I've refined my product and found my market/audience. The business world is very ok with tech start ups making zero profit and burning money for years. Maybe that's how we can view writing/creative careers too...

Thank you! I love this. I also give away my Substack posts for free, hoping readers enjoy reading them as much as I'm enjoying writing them. The best part is when they resonate with someone, and they either comment or email me to tell me. The connection is invaluable. ❤️